1/2024 Invert, always invert!

Open pdfINVERT, ALWAYS INVERT!

When Charlie Munger, the vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway and, in Buffett’s words, the architect of its business philosophy, passed away just before his 100th birthday late last year, I was just beginning to write my previous letter to shareholders. I told myself then that I would not write about Munger at the time, as I would rather leave it to those who knew him better and were more qualified to do so. Since then, however, various of Munger’s ideas and notable sayings have popped into my head again and again, and one of those led me to the subject of today’s letter.

Probably the most famous Munger quote goes like this: “All I want to know is where I’m going to die so I’ll never go there.” This, of course, was meant in jest and is not a wish that could be fulfilled. Nevertheless, it is a statement inspired by the same great Prussian mathematician, Jacobi, who advised: “Invert, always invert!” as a tool for solving difficult problems. It was precisely the advice “Invert, always invert!” that at one time made the greatest impression on me. I no longer remember the first time I heard it. Perhaps it was 20 or 30 years ago, but I would say it still holds the top position among Mungerisms. Maybe it reminds me a little nostalgically of my secondary school years when we covered proof by dispute in my beloved math class, but the “Invert, always invert!” approach can be applied generally to problem solving in almost any field of thought. It seeks to strive for good judgment mainly by collecting instances of bad judgment and then thinking of ways to avoid such situations.

Let us try and apply this to investing. Most advice and recommendations on investing pursue the goal of achieving good returns and making money, but what would investment recommendations look like if their aim was to attain significantly negative returns and to lose money? That is, if the goal were taken as the inverse of the original one? If we develop a clear understanding of these bad practices and think about ways to avoid them, or to do the opposite, then this ought to produce good investment results. This is not so easy as it might seem at first glance, because investing is a matter of probabilities, and even pursuing what seemingly and unambiguously are bad practices does not guarantee a bad outcome.

If you choose to lead an unhealthy lifestyle, for example, you may achieve a bad outcome more easily. A strategy founded on overeating, lack of exercise, minimal sleep, and exposure to risk factors such as smoking or drugs will virtually guarantee the outcome. There are no guarantees in investing, but that makes it all the more interesting. So, if we set out to lose as much money as possible, how would we go about it? I would divide the recommendations into three areas ― investment philosophy, investments selection, and decision-making process.

Investment philosophy

I would recommend to not have any investment philosophy whatsoever, to not set any investment goals, and certainly to not have any way of achieving them. I would view investing as a completely random, mindless, and ad hoc activity, especially so long as it bears fruit as quickly as possible. I would also regard investing as a race or competition with unknown opponents or with various benchmarks, however irrelevantly they are constructed. Inasmuch as patience has no place in investing and everything needs to be had as quickly as possible, a great deal of leverage would be needed, both in the portfolio (something about which we know all too well ourselves) and at the individual company level. Debt can be a relentless killer, and the bigger the debt the more deadly the weapon. I would be very inventive in my use of debt by combining the borrowing of money with a hefty mix of long and short positions, and of course the financial weapon of mass destruction – derivatives – would not be left out. I would put special emphasis on short positions. Their asymmetry of possible returns, where the loss is theoretically unlimited, is irresistible. Then, to add the proverbial icing on the cake, I would focus exclusively on investing into things which we do not at all understand. Only the Devil himself could keep that from achieving our inverted goal!

Selection of investments

Serious analyses of individual companies are the stuff of investment dinosaurs who live in the past and have absolutely no understanding of modern investing. So, we would forbid these. Also strictly prohibited would be the reading of annual reports, financial statements, perhaps even footnotes. These things lead to nowhere. We would only invest in stocks that are currently trending on social media or on YouTube. The more expensive they are, the better. After all, the price of a stock reflects its popularity in the eyes of investors, and the more popular a stock is today the more profitable it surely will be in future. It would be necessary to jump on any current trend and to churn the portfolio by making it turn over as quickly as possible. Anyone who makes only a handful of trades is simply lazy or clueless. Should it be necessary to use any actual information, then it should come exclusively from secondary sources. The pursuit of rational consideration or consistency should be avoided at all costs.

The greatest weight in the portfolio would be given to companies concerning which we have no idea what they do and no idea as to what their business models are based upon. If management itself has no clue, either, that is all the better. The ideal management team in our eyes would be one that puts itself first and foremost while remunerating itself handsomely. We would place an emphasis on gigantic stock awards to management where management bears no risk. (Note: one could elaborate upon the benefits of investing in companies run by megalomaniacs with huge egos and who produce big halo effects.)

The days when the goal of companies was to make money or achieve high returns on capital are long gone. Dogmatic adherence to low stock valuations belongs to ossified, archaic professors (Benjamin Graham) or old men whose train had long since left the station (Warren Buffett). My (anonymous) contacts on Twitter and YouTube earn much more and with much less effort in a completely different way. (Note to self: find out how). The current trend is to invest in companies that have painstakingly developed the “Fake it till you make it” model. Hopefully there will still be plenty of them in the market.

The investment horizon is an abstract concept often used by investors of advance age to confuse those around them in an attempt to appear clever. We would completely reject such a thing. Instead, we would rather stick to our most sophisticated skill, which is the art of predicting short-term market movements. It is not difficult; one just has to be fearless and go all in with one’s entire portfolio. It all fits together so nicely.

Decision-making process

A good decision-making process must be characterised by complete, 100% absence of critical thinking. Why subject our own opinions, or opinions we hear elsewhere, to any critical scrutiny? That is a waste of time and would only serve to confuse us. After all, we already know so much ourselves that we could be proud of it (true unadulterated epistemic arrogance) and the unknown would not really exist for us. Humility would be a dirty word. Self-education would be for the ignorant. Our credos would be never doubt ourselves, superficiality, dogmatism, and a black and white view of the world. Nevertheless, we would of course need to be able immediately to cast aside our belief in our own infallibility once the opinions of social media experts reached us. We would most highly value the advice and tips from those who speak anonymously, have no experience with money management, and ideally come from academia. Watching and following them would provide the map to our treasure trove. At the same time, we would not be afraid to seek out herd behaviour and deftly to engage in it. Mass hysteria is a good investment advisor. Mindless copying of other, preferably completely unknown investors would be a sure bet. Intuition and impulsive action would have to take precedence over rationality. What is rationality anyway? Just another empty notion that has no place in modern investing. Emotion – that is the real driving force. If we were to have a feeling of fear or greed, that feeling would need to be indulged, nurtured, and we should trade under its influence to the greatest extent possible. Above all, and I would particularly like to emphasise this, our main driving force in investing would have to be envy. The mother of all successful investors.

Okay, I think that is enough. When I gave the above text to my wife to read, she insisted that I write that it was the April Fool’s Day edition of the letter. So, in the interest of domestic tranquillity, I am stating that here. But otherwise, dear shareholders, I think we understand one another. This letter has been written in a lighter vein, but, even so, the main point should not be missed. If a person recognises clearly what behaviours should lead to bad outcomes, and if one succeeds in avoiding them, then he or she should increase the likelihood of good outcomes. Probability is quite sufficient, for certainty is not to be sought in investing. Although I wrote the preceding paragraphs with a slight grin on my face, I was well aware that in the past we, too, have been caught up in some of the criticised practices. A person is always learning, and we should always be learning. “Invert, always invert!” is an excellent device.

Changes in the portfolio

We sold three positions: Lockheed Martin, LabCorp, and Celanese.

Lockheed and LabCorp were two very profitable positions that also helped us when the market was in tough times. When the Chinese virus hit the world in the spring of 2020 and economies were paralyzed by the shutdown, it came as a shock to most companies. No one knew what would come next. As it turned out, for some companies the times were very difficult, they were sometimes teetering on the edge of survival. For others, by contrast, this was a period of record profits. LabCorp was one of those companies affected in a very positive way. Its profits soared to unprecedented levels, driven mainly by revenues from testing and vaccination for the Chinese virus. The share price also responded to the record profits by climbing to record highs.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, arms companies’ shares surged upwards for obvious reasons. This was due to higher expectations for their long-term sales and profits. Lockheed’s stock did not miss out on this trend. It climbed to a new record high during 2022, which was all the more pleasing because it happened in a year when stock markets were down significantly. Shares of both LabCorp and Lockheed thus reached levels that made them only modestly attractive going forward, and even their relative valuations were not appealing vis-à-vis other opportunities open to us. We gradually sold down both stocks, moved the money into other stocks, and eventually both LabCorp and Lockheed disappeared from the portfolio altogether.

Both LabCorp and Lockheed were large positions for us at the time, and their returns had a positive material impact on the performance of the overall portfolio. Celanese, on the other hand, was always a small position, and so, despite the good returns it achieved, its impact on the portfolio’s overall return was negligible. We had bought Celanese shortly after the company had announced a large acquisition of DuPont’s broad portfolio of engineering thermoplastics and elastomers. This acquisition, while strategically sound, was overpriced in our opinion. Many investors apparently thought the same thing, as the stock reacted by dropping significantly to USD 90 in the following months. This decline nevertheless seemed excessive to us, and we therefore included Celanese stock into our portfolio. At the price of around USD 150 during March of this year, we felt, first, that our original investment hypothesis of a valuation correction had been fulfilled and, second, that the valuation was roughly in line with the company’s value. We therefore sold the stock.

Events in the markets

A long time ago, when I had first noticed (about in 1989) that there existed such things as stock markets, the Japanese market was the most popular in the world. The assumption had been that the Japanese were going to dominate world business, and anyone who was not invested in Japanese stocks was just missing the boat. Then, Japanese stocks collapsed. Coincidentally, that market only reached a new high this year – almost 35 years later. That shows just how huge was the bubble in Japanese stocks back then. A few years later, as a professional working in the business, I used to hear from my American and British clients that the safest and most lucrative investments were in emerging markets. These were just waiting to crash in 1997. The investment (and speculative) community wasted not a minute in rushing into telecom and dot.com stocks, as nothing else in investing supposedly made sense. These segments of the market were in for a long and sharp dive starting in the spring of 2000. The American market was then regarded as dead in the water and everyone rushed into European stocks first, and, if that was not enough, then into commodities, financials, and Chinese stocks in light of the continued globalisation and growth of the Chinese economy. The year 2008 was a fiasco for all these stocks. Because investors have short memories, they soon rushed into Chinese stocks again and went through their crash once more in 2015. With the exception of the Japanese bubble, which I know only from reading about it, I remember all the other bubbles very well, including many smaller ones, regional or sectoral bubbles, or those involving individual stocks. I also remember how these bubbles gradually came to be, how they were pumped up, and what happened after they burst. I find them very instructive. For our own benefit, we can draw the following main lessons from them:

1. Stock market bubbles have always been here and always will be with us because they are driven mainly by human nature and that will never change.

2. They have several key features in common. First, there is a narrative, often quite rational at the beginning, that strikes investors’ imaginations. Over time, the story comes to completely dominate over considerations of company fundamentals and stock prices gradually become irrelevant. Speculative behaviour escalates as people get positive feedback from ever-rising prices. Investors lose touch with reality and rationality. There is talk of a new normal, and older investor who have experienced many such bubbles are labelled by investment newcomers as clueless and ossified. Eventually, share valuations reach quite absurd levels and, as a rule, the concentration of money in these stocks within the limelight rises along with them.

3. Nearly every bubble ends in a dramatic burst, and it is often the younger and less-experienced investors who are left to pay the proverbial piper. (If you are wondering how to tell if something is a bubble, Jeremy Grantham of GMO, who has been studying bubbles for a long time, has a good definition. He defines a bubble as a condition where the current situation has deviated by more than two standard deviations from its trend.)

4. The prices of stocks that have gone through a bubble that has burst are usually very slow to recover and many will not survive the bubble’s breaking. This is a very important rule. Japanese stocks took decades to recover. Technology stocks either took an extraordinarily long time to recover from the 2000 bubble (e.g. 15 years in Microsoft’s case) or are today already long gone. Commodity stocks still have not regained their pre-2008 position, and Chinese stocks remain today a shadow of their 2007 glory.

5. Against the backdrop of bursting bubbles, other stocks or sectors often do very well. This is partly due to their much more attractive fundamentals, some (at least momentary) sobering of investors, or the pivoting of money from bubble to non-bubble stocks.

Why am I writing this? The current situation in markets, and especially the US market, displays some characteristics that are common to bubbles and urge great caution. This is evident in the record concentration of money in a handful of the largest U.S. companies. (The top 10 companies make up 33% of the index, but only 23% of its earnings.) Never in history has this concentration been so high. The valuations of these stocks as a whole are also high (the Top 10 have an expected P/E of over 30 for 2024). It is difficult to imagine that these stocks will keep on delivering above-average returns over the next decade. At their size, their revenue growth will continue to slow, pressure on their margins will persist, and it is difficult to imagine that the multiples at which these stocks are presently trading can expand even further.

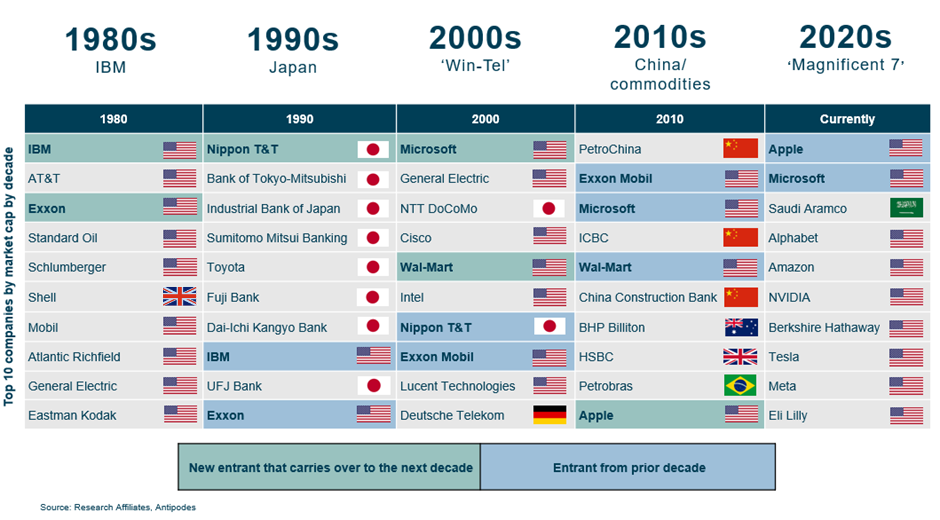

History provides an interesting perspective here, too. The following table shows the world’s largest companies over the past several decades. Once a company gets to the top, with few exceptions, it struggles to stay there. There are three main reasons for this. Size is always a brake on further growth, being at the pinnacle often goes hand in hand with high valuations, and the world is always changing. Even the biggest successful companies gradually get replaced by new ones.

The predominant narrative of the time can be observed in the composition of these rankings. Around 1980, the prevailing belief was that the peak of oil production was nearing, and that the best-managed companies were American. Ten years later, it was assumed that Japanese companies would dominate the world. Then there was a bet on dominance of the U.S. telecom business, later again that oil production would peak, and afterwards that China would take over the world. Yet subsequent developments showed that, from an investment point of view, it would have been best to gradually move away from U.S. extractive companies, then Japanese banks, then U.S. telecom and dot.com companies, and still later Chinese and commodity stocks. The current narrative is that the world will be dominated by large U.S. technology companies due to their near-monopoly position and advances in AI. It remains to be seen whether this narrative will show the best course for investing or whether this will be a replay of what has happened in each of the previous decades.

You can probably guess that these are the reasons why we have none of the currently largest stocks in our portfolio, with the exception of Berkshire Hathaway. This is because, as a whole, we expect relatively unattractive returns from them going forward. The stocks we do have in the portfolio trade at a fraction of the earnings multiples of the largest ones, and collectively they have more growth potential, as can be seen in the Fund’s returns in recent years. The sizable representation of the largest U.S. companies in the index and their high valuations make the entire index expensive. When we look at the valuation of the U.S. market after excluding the largest companies, however, it appears quite reasonable in terms of the average (with an expected P/E of 18 this year). Among the many companies there, it is possible to find a number that are very attractively priced. This points to a big advantage of active investing, because an active investor is not a slave to the composition and valuation of the index. Rather, one can construct a portfolio with much less risk and much greater expected return. Moreover, because our fund is not American but global, the rest of the world, with its generally less-costly stocks, also provides an interesting playing field for our investing while at the same time not suffering from a similar concentration of large and dearly priced companies as does the American market.

Daniel Gladiš, April 2024

For more information

Visit www.vltavafund.com

Write to investor@vltavafund.com

Follow www.facebook.com/vltavafund and https://twitter.com/danielgladis